The Heartbeat

By: Adam Stack

Table of Contents

Introduction

On Tuesday, September 5, 2006, Alan Mulally arrived in Dearborn, Michigan, for his first day of work as the CEO of Ford Motor Company. The company he was taking over was preparing to post the biggest annual loss in its 103-year history just a tiny $12.7 billion—and a foreign rival’s sales had surpassed it for the first time. A public declaration that an American icon had squandered its deep customer loyalty and bankruptcy seemed all but inevitable.

In a scene that could have been right out of “Ted Lasso,” a TV show where an American football coach moved to England to coach a soccer team, Alan arrived for his first day of work with no automotive experience—a point that made Bill Ford, the man responsible for ensuring Ford’s long-term survival, a little uneasy. However, the industry’s more experienced executives were disinterested in a suicide mission and had turned down the top job.

But what Alan did bring was far more valuable than automotive experience: simply a few sheets of paper outlining his “Working-Together” management system, his life’s work.

“Working-Together” is a system that Alan perfected while building some of the world’s most complex and profitable products. The cornerstone of the system is a weekly meeting called the Business Plan Review (BPR) which would run from 7:00 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. It would include all business and functional leaders across the globe. The meeting would align the team around one plan, identify issues, and commit to moving the plan forward.

In 2008, the world fell apart. The financial crisis wreaked havoc on the American economy, and auto sales plummeted by forty percent.

Headlines from September 2008 Credit: Richard Levine /AlamyThe reigning kings, Chrysler and GM, found themselves begging Congress for a financial bailout, and experts thought it was just a matter of time until the Ford team cried uncle and accepted a bailout. The prevailing view was that despite Ford’s progress, there is only so much an organization could control in a crumbling industry.

What so-called experts and investors (like Kirk Kerkorian, the billionaire investor who dumped his Ford stock) missed was that the Ford team had mastered the BPR meeting. Throughout the crisis, Ford worked together, seized market share, and began a climb to regain its stature as a great company.

Three years after its first BPR meeting, Ford reached profitability and grew its net income by a jaw dropping $17.5 billion.

And in an ironic twist, despite $50 billion in government bailouts, the CEO of GM, who had offered to teach the “novice” Alan about the automotive industry, drove his company into bankruptcy, parking it alongside Chrysler. And Kirk Kerkorian who bet against Alan and the Ford team lost over $400 million dollars.

In 2014, after enough time had passed to judge the turnaround’s sustainability, Alan was recognized by Forbes as one of the greatest leaders in the world, simply for being a humble leader who saved an American icon by teaching his team how to win—a true Level 5 leader.

Do Meetings Matter?

But did Ford’s turnaround have everything to do with meetings, or were other factors at play? A fair question, a common one, and one I had myself.

In Ford’s case, to save the company, they took out a $24 billion home improvement loan to rebuild it. They standardized production across models, sold non-core brands, renegotiated labor deals, matched production to demand, and created new best-in-class vehicles that customers loved.

Interestingly, before the transition, Mark Fields, then Ford’s president of Ford’s Americas division, had made progress in many of these areas using a plan called “the Way Forward.” Derrick Kuzak, vice president of global product development, started streamlining development, and Bill Ford, chairman and CEO, recruited great people. Despite all their success, Ford was still losing billions of dollars a quarter.

Ford faced the challenge that all big projects face. Big projects are complex organisms, just like our bodies. Each team is a key organ. An organ might be healthy and strong, but without a robust circulation system, the performance of the whole suffers. Ford needed a communication system to connect the teams, build on each other’s efforts, and circulate information. That was one of the key pieces Ford was missing before Alan arrived. That was the requirement that the BPR meeting filled.

But I hope you want to raise an excellent point: Ford had meetings before Alan arrived in Michigan. GM had meetings, and Chrysler had meetings, and both crashed and burned. The difference lay in how the organizations ran and used meetings.

At GM and Chrysler, meetings were similar to the average boondoggle we are all used to. The only thing their meetings were great at was wasting people’s time.

In these meetings, team leaders would proudly report the impressive work their team did last week—with each leader trying to one-up the last. These so-called “leaders” never made a bold commitment to future goals. That was simply too risky. They could be held accountable for specific results—that is, if anyone was actually paying attention. And under no circumstances would anyone discuss a problem. Of course, from time to time, some brave soul would venture out of bounds into an area of substance, only to hear the words “Take it off-line,” the corporate code words for “Let’s never talk about this again.”

This is worlds apart from meetings at Ford and other big projects I’ve studied called Great Projects. If you are unfamiliar with my larger body of work a Great Projects is a Project at the upper end of an organization ability. When finished it transforms the organization and often shapes an industry and changes the world.

The Great Project meetings accelerated progress, drove accountability, and boosted productivity. They engaged in healthy face-to-face conflict and were full of bold and specific commitments in service of the goal. Over the long run, they forged individuals into a team and showed them the trill of winning together.

If you are a student of the Ford turnaround (as all CEOs should be), you know Alan has given the world a great gift and spent a lifetime refining and articulating the importance of his “Working Together” system and BPR Meeting.

However, it is essential to know that Ford is not an isolated case, and meetings like the BPR are not an individual leadership style unique to Alan; they are an enduring trait of a successful Great Project. In his book Creativity, Inc., Ed Catmull, the CEO of Pixar and leader of the Great Project that created the world’s first feature-length computer-animated film, devoted a portion of the book to the importance of meetings at Pixar.

Ford and Pixar are not alone; research has shown that meetings played a central role in 100 percent of the Great Projects but were overlooked in a set of audacious projects that should have become great but failed.

Over time, it became clear that the Great Project meetings had little in common with the average meeting we all know and hate. They were so different you could hardly compare the two. Out of this insight, the Great Project meetings became known as Project Heartbeats. All projects have meetings. All originations have meetings. All teams have meetings, but only Great Projects have Heartbeats.

The name reflects how reliant the projects were on their unique breed of meeting. If they stopped having them, their project would likely die very quickly—just like if our heart stops beating, we die very quickly. But the opposite is also true: if we are fit and strong and work hard our heart becomes stronger and stronger and propels us forward, fast and faster.

But even after being confronted with this evidence, most people think meetings are a waste of time…and to be fair, most are.

The Need for a Framework

The challenge with meetings is that the majority of them are awful. Because we have all attended so many bad meetings, it is almost impossible to imagine that they could be a key factor in success. In one conversation with a CEO, he said, “Why are you studying meetings? I hate meetings and encourage my team to have fewer of them. Most are a waste of time.”

That CEO was being dramatic for effect. Being an ambitious leader, like the CEOs who led the Great Projects, he knows he needs a way to coordinate efforts. And despite all of their flaws, meetings are uniquely suited for that purpose.

His comment comes from a deep frustration. He would love to run a Heartbeat pointed toward his organization’s biggest goals; but, like most leaders, running productive meetings is an elusive goal that happens by chance rather than design. And popular advice does little to help.

With that CEO in mind, I set out to build a simple, repeatable, and teachable framework based on the Great Projects to turn average meetings into a Heartbeat. I started with one Great Project, systematically analyzing and coding each meeting technique. Then, I repeated the tedious process for each project in the Great Project study. The outcome was an Everest-sized mountain of techniques that spanned 110 years—some comically outdated, some industry-specific, and some shockingly enduring.

Then I boiled down the mountain, melting away the snow and ice (such as personal style), looking for the techniques used by all Great Projects. The outcome was five key ingredients for turning a meeting into a Heartbeat.

The Recipe of the Heartbeat

A Heartbeat is a gathering of team members that accelerates progress toward accomplishing a clear and compelling goal. To create this outcome, you need to know and master the application of five ingredients.

1. Epic Opening: Set the tone, get the team’s attention, and make them care.

2. Commitment: People make bold and specific commitments in service of the project or goal.

3. Recap: You recap, record, and share what people commit to and the decisions that were made in the Heartbeat.

4. Focused: Everyone is 100 percent focused throughout the Heartbeat and contributes to the group’s success.

5. Top-down: The leader sets a high bar and holds people accountable.

Below, we’ll explore each Heartbeat ingredient in the context of a different Great Project. This will give you broad exposure to how other organizations have applied the ingredients and help bring the Heartbeat to life in your organization.

Meeting Myths

The first step to running a Heartbeat is to wipe the slate clean and dispel a set of common meeting myths that often lead to unproductive meetings. If you are unfamiliar with these myths, transforming meetings into a Heartbeat will be impossible.

Myth 1: Meetings must have an agenda.

Reality: Heartbeat leaders start with the objectives they hope to achieve. Then, they decide if an agenda will help accomplish those objectives. Agendas lead to structured conversations, which can be good or bad.

Myth 2: Meetings should be fun.

Reality: While meetings can be fun, that is not the goal. Heartbeats are like intense workouts: they may be challenging but yield rewarding results.

Myth 3: Meetings should motivate people.

Reality: Meetings that concentrate on motivation overlook problems and shy away from holding people accountable. Ironically, this approach demotivates motivated people.

Myth 4: There is one right length for a meeting.

Reality: Changing the length of a meeting (e.g., from 30 minutes to 25 minutes) won’t fix bad meetings. Heartbeats start with what needs to be accomplished and then set the time frame for the meeting.

Myth 5: Great Project teams spend more time in meetings.

Reality: Average meetings increase the number of meetings, increasing total meeting time. Heartbeats, like the BPR meetings, reduce total meeting time.

1. Epic Opening

Make your team care and get them engaged. State the goal the Heartbeat will help achieve and its purpose in a clear and compelling way.

Project Example: Moon Landing

Looking back, we view landing a man on the moon as a goal the country was 100 percent committed to. But, in reality, it was closer to 50/50.

In the 1960’s America was in turmoil. The Vietnam War, anti-war protests, political assassinations, and the civil rights movement marked the era. It was unclear if the next president would scrap the moon program when he took office in a few months.

This was the backdrop for a one-on-one meeting between Chris Kraft, a senior NASA leader, and Gene Kranz, the man responsible for the details of the moon landing. With the energy and speed of a rocket, Chris launched into the purpose of the meeting.

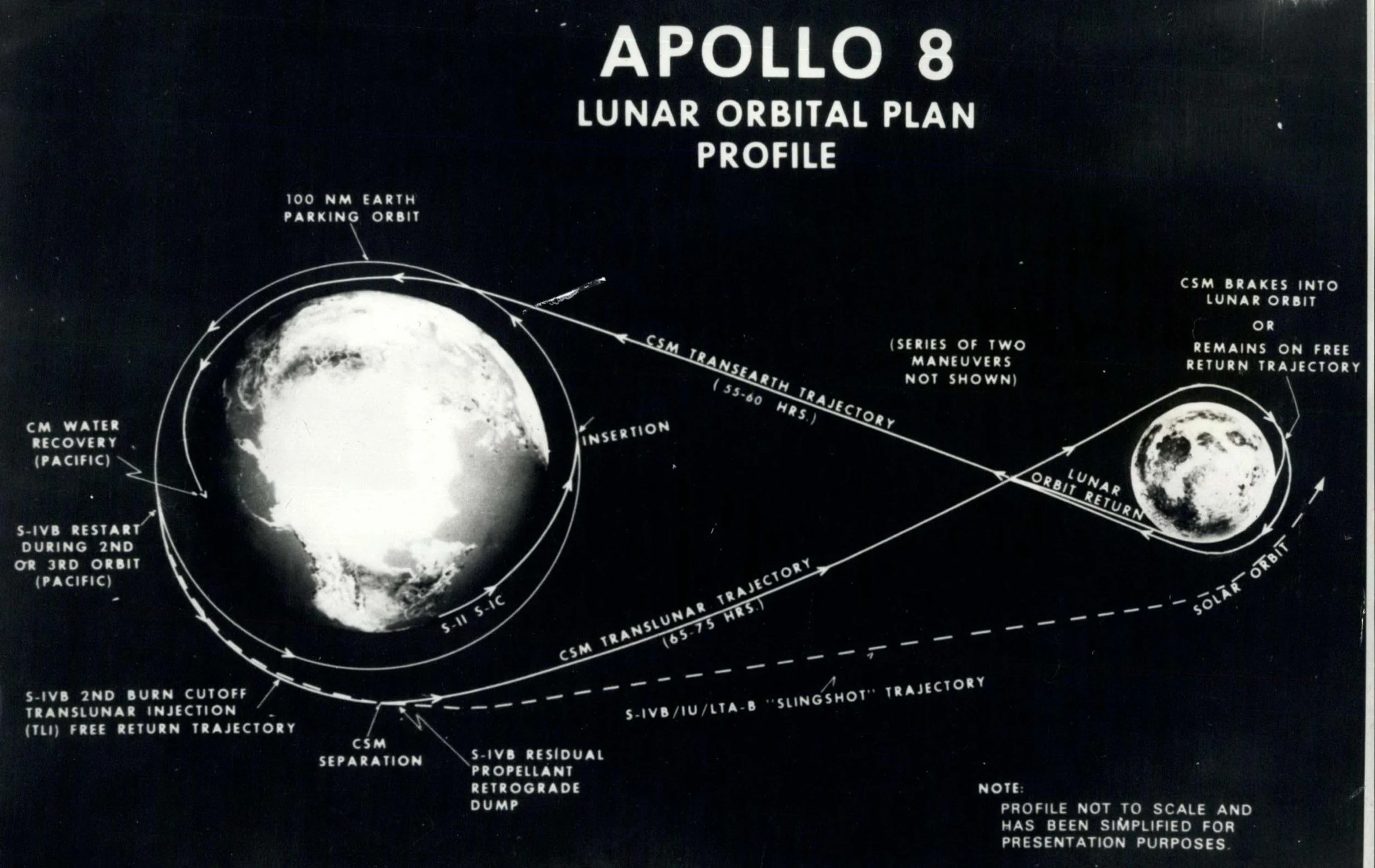

“Gene, George Low wants to fly a mission to the moon this year. He believes he can have a CSM (the spacecraft) available in December. George wants to drop the E mission from the schedule and then use the Apollo 8 crew for a lunar orbit mission…I will need your assessment by Monday, if not earlier.”

Apollo 8 mission profile. Credit: Keystone Press /Alamy Stock photoNASA’s big boss was essentially saying that they were running out of time and that they were going to abandon the conservative and incremental approach they had used for the last eight years. They would cut the safety missions and fly around the moon before the new president took office.

The goal was to tie the new president’s hands by getting so close to landing on the moon that it would be foolish to cut the program. And Gene’s team was given three days to figure out how to pull it off.

As Gene recounted in his autobiography, “The shock on my face must have been evident.”

This story illustrates the impact of an epic opening—it floored Gene, a former fighter pilot. The opening set the tone and pace for the meeting, got him sitting up straight, fully engaged, and prepared him for what was coming. It grabbed him by the gut and made him care.

This is a master class in an epic opening. Chris had many options for opening this meeting. He chose the one that would resonate with Gene, who was deeply involved in the details, and Chris knew that details, not the common Kennedy proclamation, would grab his attention. He also did not dance around—it was an order, not a discussion. To be clear, I’m not saying an order is better than a discussion. Simply put, if you are giving an order, make it clear.

By Monday, NASA had a new launch schedule, and on Christmas Eve 1968, just seven days before the end of the year, the first Apollo mission orbited the moon, guaranteeing NASA would get one shot to land on the moon before the program could be cut.

2. Commit

The past is fixed; the future is made. Everyone commits to clear and specific goals.

Project Example: Women’s Right to Vote

In 1920, the final act of a half-century battle to grant 25 million women the right to vote was going to be written in the heart of Tennessee.

Tennessee had become the last hope for the suffragists to get the 19th Amendment added to the United States Constitution. To have an amendment added to the Constitution, three-fourths of states needed to vote to ratify it, essentially accepting that it should be the law of the land. Similar to a national election, the swing states determine the outcome and Tennessee was the last swing state to vote. If they voted to ratify the 19th Amendment, women’s right to vote would be added to the Constitution of the United States. If Tennessee voted against ratification, the amendment would be placed in a filing cabinet and forgotten.

On one side, you had a team of well-funded, powerful lobbyists, fighting to protect the status quo. On the other was a team of suffragists trying to pull America forward. In the middle was a group of state representatives amid a high-stakes game of tug-of-war.

Left to right: Mrs. Wood Park, Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt, Mrs. Helen H. Gardner: second row, Miss Rose Young, Mrs. George Bass, and Miss Ruth White. Image courtesy National Archives. 1917.The lobbyists, masters in the art of backroom handshake deals, had organized a pop-up speakeasy called the “Jack Daniels suite” on the eighth floor of the historic Hermitage Hotel, a stone’s throw from the state capitol building.

In the suite, whiskey flowed like water (despite Prohibition being the law of the land). Each time the door swung open, a wobbly and jovial representative emerged from a thick cloud of smoke with pockets full of cash, confident his reelection was secure.

Meanwhile, in room 309 down a few floors below, a different meeting had long ago wrapped up, with its attendees now resting in bed, except for a few women assigned to keep tabs on the speakeasy door.

A team of women had packed into Carrie Chapman Catt’s tiny hotel room, filing in like well-trained soldiers. Catt, their Level 5 leader, one in a long line of leaders who had dedicated their lives to winning women’s right to vote, was handed the baton for the final lap.

The informality of the meeting’s setting masked the events that were about to start. In rapid succession, the women discussed tomorrow’s plans and turned those plans into tasks, occasionally returning to the previous day’s work whenever a representative emerged from the smoking room looking a little too happy, a sign the ladies had learned meant that the lobbyists had flipped that representative.

As the clock ticked down, the suffragists lost majority support for the amendment. Like all Great Projects, the team responded to the setback not by finger-pointing, but by making bold and specific commitments they would carry out the next day.

· Carrie Chapman Catt: I will hire a private investigator to track down who was paying for the lobbyist who was peeling away support for the amendment.

· Anne Dudley: I will use my relationship with local reporters to soften the blow of losing the majority support and push our narrative.

· Anita Pollitzer and Catherine Flanagan: We will board trains in the morning to track down and deliver Hooper, Taylor, and Littleton to Nashville. They can help shore up the base.

Day in and day out, week by week, this fast-paced meeting was repeated — discuss, adjust, assign, sleep, complete — discuss, adjust, assign, sleep, complete.

Using this relentless process, the team of suffragists dismantled those late-night handshake deals one by one. Then, on August 18, 1920, from her modest hotel room overlooking the state capitol, Carrie Chapman Catt would hear thunderous cheers of her solders sitting in the capitol building observing the vote. The 72-year epic battle that began on August 3, 1848, in Seneca Falls, New York, had finally been won. The women of America had taken what should have always been theirs - the right to vote.

3. Recap

Recap the items people committed to: Who, What, and When, as Vern Harish says. No more, no less.

Project Example: IBM 360

In the early 1960s, computers were niche tools. They were insanely expensive and specific to an industry. It’s hard to imagine today, but if you outgrew your current computer, the new one would cost millions of dollars, and you would have to rewrite your applications to work on the new machine. The concept of a standard operating system had yet to be invented, making cross-compatibility impossible even within one company.

However, the team at IBM wanted to change that. They envisioned creating a standard operating system that would enable businesses to upgrade as they grew and allow the creation of general-purpose applications, like “Excel” and “Word,” that would provide value across industries and work across computer models. They wanted to create the modern computer architecture that we take for granted today. It would be called the IBM 360 family of computers.

The catch was that it would cost $5 billion to bring to market, twice IBM’s annual revenue. This would be the equivalent of IBM spending $120 billion to bring a single product to market today. It would be the largest privately financed commercial project ever undertaken.

To many insiders and all outsiders, it was a ridiculous bet. Competitors lacked the cash to develop a competing offering. It could refine already successful products for years to come, and the current business model was lucrative and thriving.

But that was not the IBM way. On April 6, 1964, Thomas Watson Jr. announced the IBM 360 to the world, and IBM started a self-imposed race to the finish line. After the announcement, orders for existing products dried up. Customers preferred to wait for the 360. If the project were late, it would not be pretty. Best not to think about it.

With this pressure, how would you respond after discovering that, due to a communication mistake, you would have to scrap two years of work (on a four-year project) and rewrite the operating system?

If you’re Fred Brooks, one of the great technologists of the twentieth century, and the 360 project leader, you’d improve meeting notes. Yes, that’s right. Probably the most technologically advanced company at the time decided that the solution to a billion-dollar problem was shorter meeting notes. They eliminated the detailed play-by-play meeting notes and moved to crisp notes that outlined commitments, decisions, and changes.

IBM made it to the finish line, and the 360 family of computers was a blockbuster financial success, and was hailed as one of the top 100 technological developments of the twentieth century.

4. Focused and Helpful

All team members are 100 percent focused on the Heartbeat, connecting dots, and looking ahead to help achieve the organization’s goal.

Project Example: Ford’s Turnaround.

Early in Ford’s turnaround, a hot new car named the Edge began rolling off the assembly line. Coming off a $5.2 billion quarterly net loss, the Edge would slow the bleeding, delivering critical cash for Ford’s turnaround and signaling to Wall Street that Ford was back in the game.

However, corporate turnarounds are not like fairy tales. A small issue was discovered days before the Edge was set to ship to dealerships across America. It was not the type of issue that would trigger a recall, just a small issue that would annoy customers, cause a few headaches for deals, and hurt the company's goal of building viaticals customers loved. This type of issue would have been buried in the past.

Mark Fields, then president of Ford in the Americas, made the bold call to delay the launch.

In the weekly business plan review (BPR) meeting, Fields informed the team that his part of the plan to save Ford was off track.

In the old Ford—the one that lost $5 billion in one quarter—Mark’s lousy luck would have been seen as a ripe opportunity to secure a promotion. The question would have been: Who could push Mark off a cliff first and take his job?

But this was the new Ford, despite the company being moments away from smashing head-on into a brick wall, killing the executives’ careers on impact. The only question that day was who could help Mark. The question was not “What happened?” or “Who is to blame?” delivered with the rage one might expect. It was “Who can help?” delivered with Alan’s trademark can-do attitude. Bennie Fowler, head of quality at Ford, stepped forward, committing his team to help get the plan back on track and putting his reputation on a line for a problem that was traditionally not his.

This led to special-attention meetings to dissect the problem, create solutions, and ensure their implementation. With the nimbleness resembling a small, thriving enterprise, the issue was resolved, and the Edge was shipped to dealers a few weeks later, marking a turning point for Ford.

Like all Great Projects, this simple routine worked because it drove accountability. Mark Fields and Bennie Fowler stood up in front of their peers and committed to fixing an issue that would affect everyone in the room. At the same time, it brought the team together. Peers were 100 percent present and 100 percent focused on Fields’s update. What needs to be adjusted? Marketing, cash flow? Any liability? Who needs to know? Unions, dealers, partners? How can we make up ground? How can we buy them time? These types of questions circulate in a Heartbeat when everyone is focused.

5. Top-down

The quality of a Heartbeat is set by the leader.

Project Example: Race to the South Pole

In October 1910, one of the greatest races in human history got underway. Two teams competed to be the first to reach the South Pole. By the end of the race, one team returned home victorious, and the other lay dead just a short distance from the ship waiting to take them home.

The Scott and Amundsen expeditions crossed paths in the Bay of Well on February 4th 1911. Scott's ship Terra Novacan be seen in the background Photo courtesy of the National Library of NorwayOn one side, you had Roald Amundsen, a simple man from Norway, who met regularly with his team to discuss plans and commit to each other to deliver their parts of the plan.

On the other side, his competitor, Robert Falcon Scott, a heroic leader built for the history books. Scott, an accomplished former naval officer, viewed meetings as a waste of time. He preferred the expediency of emerging from his sleeping quarters, confidently giving orders, and marching south to victory. After all, they were in a race, and speed mattered.

On March 8, 1912, the Daily Chronicle in London reported that the South Pole had been conquered. The headline was supposed to read “Robert Falcon Scott Conquers the Pole.”

The problem was that just before that headline was written, Scott had reached the pole only to discover a Norwegian flag placed by Amundsen, with a set of flags radiating out in each direction as far as the eye could see—a brilliant team effort to ensure no one could dispute which team had reached the true South Pole.

Imagine yourself in Scott’s shoes. Imagine the feeling of arriving at the pole, exhausted, discovering, almost two years after leaving home, that you had lost the race. Imagine realizing that your competitor had enough time, energy, and supplies to march in every direction as a safety measure. Any reasonable person would ask what they did differently.

But Scott, right up to his last breath, seemed allergic to other people’s ideas. Scott would march his team to their death. Evans, Oates, Wilson, Bowers—one by one, they would fall to Scott’s hubris.

On March 29, 1912, Robert Falcon Scott penned his final journal entry before closing his eyes for the last time: “We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.”

But is that the whole story? Maybe Scott simply had awful weather. In their book Great by Choice, Jim Collins and Morten T. Hansen illustrate that the two expedition leaders were a “near-perfect matched pair.” They started within days of each other. They faced similar weather conditions. They were of similar age and experience, and both had visited Antarctica before. After building on Collins and Hansen’s groundbreaking research, I discovered one additional similarity—over the course of the expedition, Scott and Amundsen both made awful decisions.

Scott was killed, but not by a freak storm or accident—both justifiable endings racing for the pole. Scott and his team died a much more tragic death. Scott used a two-team approach. A main team would head out of base camp, carrying minimal supplies. A support team would follow and restock a set of camps with food. Then, the main team would pick up these supplies on the return journey—a brilliant strategy. It allows the main team to travel at a blistering pace and conserve energy. The challenge with this strategy is that it requires flawless coordination, communication, and execution to pull it off. It requires meetings.

When Scott’s team reached the first set of supply depots on their return journey, they realized that each depot was slightly understocked, lacking the required calories to get them home. Their calorie deficit grew as they raced from one depot to the next. They became weaker and slower. Maybe they knew it, or perhaps they didn’t, but no supply depot would save them. They were as good as dead; it was just a matter of time. Why? The two teams never met to discuss the required calories, a critical point for pulling off the two-team approach.

Like Scott, Amundsen was a confident, driven, and accomplished leader—critical yet dangerous traits in one package. However, unlike Scott, Amundsen built a team of experts who could protect him from himself and created a forum to build a great plan. Over meals (their perfected meeting forum), he shared plans, helped each team member understand their role in the big picture, and demanded that they speak up if they had a productive different view.

Together, the team built a plan. That plan won the race. The point of this story is this: the leader of the team determines the quality of the meetings, or if meetings happen at all.

If you are working on a truly Great Project, it will be full of complex problems that, if not resolved, will likely kill the project and possibly your career or organization. While many issues and opportunities can be resolved in an email, many require teams to meet, discuss, debate, and commit to a specific direction. Be like Amundsen, not Scott.

What Is Not in the Framework

If you are familiar with the Project Heartbeats in this article, you will quickly point out what is missing. To clarify, each project had different rituals and practices as part of its Heartbeat. For example, many of the projects included team updates, sales forecasts, and company news, but these elements were not present across all Great Projects. You can include other items so long as they enhance the potency of the five Heartbeat ingredients. I like to think about these extra ingredients as flavors. They enhance a heartbeat but they are not required.

Building a Heartbeat

The Heartbeat term was coined by my friend and author of Good to Great, Jim Collins. After I explained to him how the Great Projects used meetings, he mentioned that it sounded like a heartbeat.

The heart, in its most basic form, is a pump. With each beat, it pushes blood through our bodies, carrying oxygen to every cell. After delivering its oxygen, the blood returns to the heart, sending it to the lungs to pick up more oxygen. Around and around the circle goes.

This is how Great Projects use meetings: They link a set of meetings that all use the Heartbeat framework to form the communication system. Instead of blood, these meetings pump critical information through the project, flowing to and from leadership teams. Decisions, schedules, problems, changes, and commitments are always circulating and pulsing from an individual team throughout the organization, driving accountability and pushing the project forward.

Do you need a Project Heartbeat? Absolutely not. There is a long list of average projects that had average meetings that produced average results. This article is for people interested in accomplishing a Great Project, like:

Thomas Watson Jr: IBM 360

Alan Mullaly: Save the Ford Motor Company

Carry Chapman Catt: 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution

Ed Catmull: Toy Story, the first feature-length computer-animated film

John F Kennedy: Put a Man on the Moon

Roald Amundsen: Race for the South Pole

I’m sure that is you. In your next meeting, start simple and master the Heartbeat recipe:

1. Deliver an epic opening.

2. Commit to action.

3. Recap what is expected.

4. Stay focused and helpful.

5. Top-down.

As you start this journey, move with urgency, but be patient. It took the grand master of meetings, Alan Mulally, months to teach and implement his meeting framework at Ford. Using one ingredient is better than none, but the Great Projects mastered them all.

Once complete, you have built a communication system—like the world’s Great Projects. Then, the question is: What will you do with it?

My greatest hope is to be writing about your Great Project in the future.